Decoding Science 005: Collaborative Human-AI Chemistry, Novel Materials for Direct Air Capture, Automated Laboratory Documentation, and Democratizing AI in Science

Welcome to Decoding Science: every other week our writing collective highlight notable news—from the latest scientific papers to the latest funding rounds in AI for Science —and everything in between. All in one place.

Good morning. We’re playing around with the structure of Decoding Sciences’ newsletter. Let us know what you think!

What we read

PRISM: Capturing the Invisible Art of Scientific Practice [Henry Lee, Off Media, July 2025] - HJ

Scientific protocols are often devoid of important tacit knowledge because papers describe what researchers did, but rarely capture how they did it with sufficient granularity. Things such as the precise pipetting angle or the specific visual cues that indicate culture contamination remain invisible: “scientists know that papers shaped by publication pressures often portray successful outcomes, rather than the countless micro-decisions and adaptations that made success possible.” This can then cause unforeseen delays for researchers who are following the same protocol as they work to rediscover methodological nuances.

To circumvent this problem, Cultivarium has developed PRISM – an AI-powered lab assistant that transforms static protocols into “a multimodal record of scientific practice.” Researchers wear glasses that record audio and video data while they are conducting an experiment. This raw feed is then processed via the model into a step-by-step process that can be read or watched for accurate reproducibility.

Beyond the immediate documentation benefits, this tool also generates training data that could be used to build truly autonomous lab agents: “AI systems that not only execute predefined protocols, but can also adapt to the unexpected, recognize when something isn’t working, and even generate novel approaches to experimental challenges.” [See a demo here]

AI for Scientific Discovery is a Social Problem [Channing et al., arXiv, September 2025] – PL

Channing and Ghosh from HuggingFace argue that the democratization of AI for science requires treating it as a collective social project. The paper argues that there are four critical barriers to its democratization and four potential solutions. This is not an exhaustive summary of the paper, and for those interested, we encourage a full read.

Barriers:

Community dysfunction that undermines collaboration:

AI Scientists could become useful co-pilots, but are a counterproductive direction to pursue and to scientific progress as it devalues expertise and contributions of human scientists whose creativity and knowledge remain essential. It also oversimplifies the complexity of scientific practice which is not only about predictive accuracy but also on careful validation, contextualization and theoretical integration, and finally, also undermines science’s purpose: the cultivation of human understanding, not only providing solutions.

Collaboration failures that arise in differences in priorities: for instance, domain scientists care about mechanistic understanding and experimental validation, while ML researchers focus on predictive performance and computational efficiency.

Misaligned research priorities targeting narrow applications over upstream computational bottlenecks:

Publication pressure and grant cycles create incentives in the scientific community to fragment and solve domain-specific problems, rather than collectively mobilize around computational bottlenecks.

Data fragmentation due to incompatible standards

Hoarding data in proprietary formats, lack of incentives for researchers to focus on data curation and harmonization, result in datasets locked in incompatible silos.

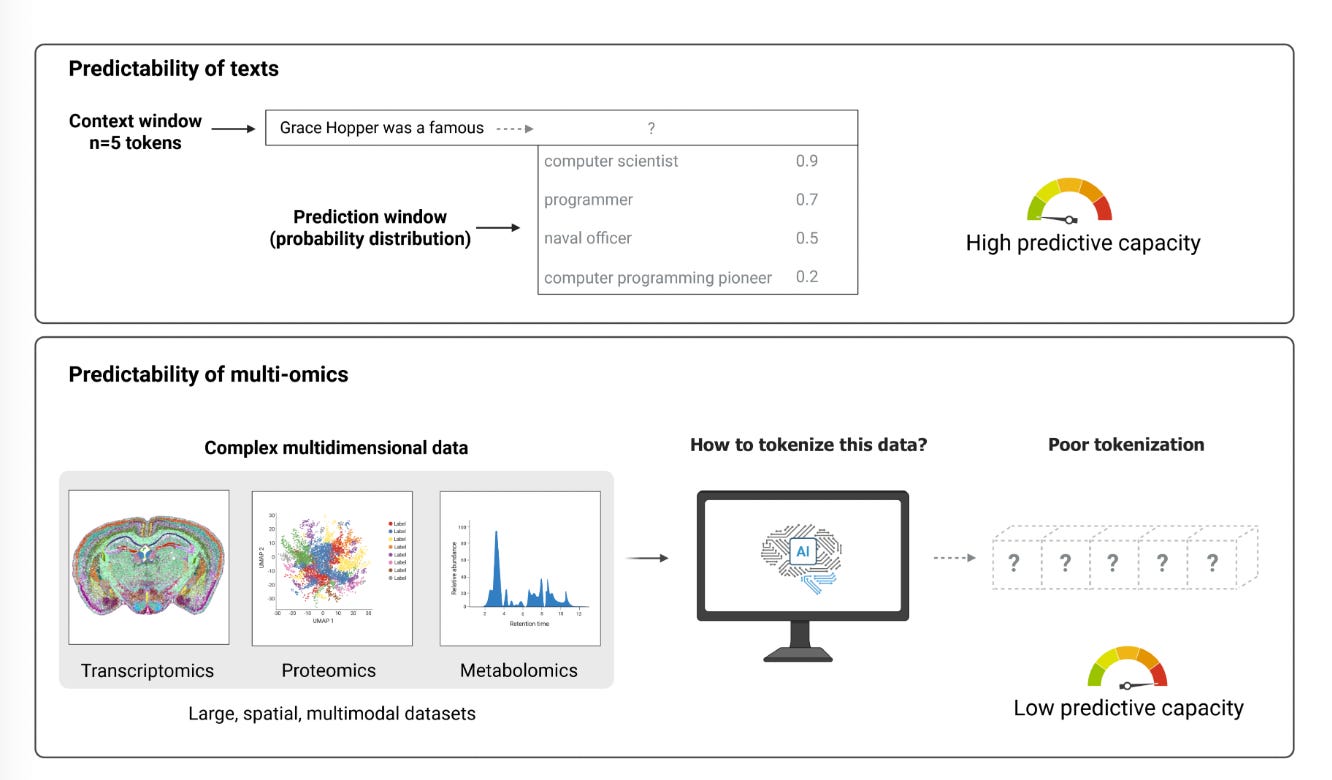

The multimodal, spatial and temporal relationships in scientific datasets resist straightforward tokenization approaches, resulting in poor predictive performance despite the scale of the underlying data.

Infrastructure inequities concentrating power within privileged institutions

Academic researchers face a lack of technical infrastructure, which is even more pronounced when compared with institutions across the world.

Solutions:

Strengthening collaboration and education across communities via standardized interfaces and APIs, community-driven development and training of domain specialists into ML specialists, and vice versa.

Structuring upstream challenges, such as the Vesuvius Challenge & DREAM Challenges, and shared benchmarks.

Standardizing and curating scientific data for broad reuse such as the standardization via file formats like CSV lower barriers to collaboration, but also through the development of architectures for scientific data (such as graph neural networks molecular and materials applications by modeling spatial relationships or physics-informed neural networks which incorporate domain knowledge into model design).

Building accessible and sustainable infrastructure through the sharing of, not just trained models, but entire scientific AI pipelines, as well as building community-owned infrastructure and sustainable funding.

Community & other links

AI models are using material from retracted scientific papers [Ananya, MIT Technology Review, September 2025]

What we read

The Open DAC 2025 Dataset for Sorbent Discovery in Direct Air Capture [Sriram et al., arXiv, September 2025] - IVdB

When thinking about direct air capture (DAC) we like to think solutions will fall out of the sky to vacuum the vast quantities of pollutants humanity exhausts on a daily basis. In the case of the newly updated Open direct air capture dataset (ODAC25) solutions might not fall out of the sky, but they could appear out of thin air.

Carbon dioxide accounts for ~76% of all greenhouse gases emitted [1]. Rather than dreaming about vacuum-cleaning solutions, the most realistic approach is to start at the source: the CO2 emitting factories. This work, released from Sriram et al., can have an important impact in providing solutions - in the form of rationally selected complex metal organic framework (MOF) materials. Metal organic frameworks are crystalline porous materials linking metal ions to organic ligands. Their high surface area networks with tunable pore size and chemistry make them ideal for active coatings and high-energy reactions.

Building on the previous ODAC23 released version [2], Sriram et al. expanded the dataset to: 1. introduce two new species of absorbents, 2. simulate materials in more realistic conditions, and 3. add chemical diversity to MOFs. First, along with CO2 and H2O, the addition of nitrogen and oxygen allowed accounting for surface oxidation. As is the case with copper roofs turning green from oxidation, so is accounting for MOF spin- and oxidation states relevant to prevent material corrosion. Introducing oxygen into simulations allowed screening of previous adsorbent-material interactions that would have not been accounted for in ODAC23.

Second, in accounting for oxidation states MOFs can be selected for highly specific applications; any that may suffer from spurious oxygen dissociation - where redox reactions can occur - will be flagged for further atomistic or experimental inspection. Performing high-energy Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations also allowed accounting for non-relaxed states of adsorbed molecules. These higher energy states are relevant for predicting an adsorption isotherm: a curve that allows seeing how much gas each MOF can adsorb at different pressures. Together, introducing oxidation states and making isotherm sampling possible has ensured that more realistic MOFs are put forth for experimental testing, and higher specificity may arise for environmental conditions they are exposed to.

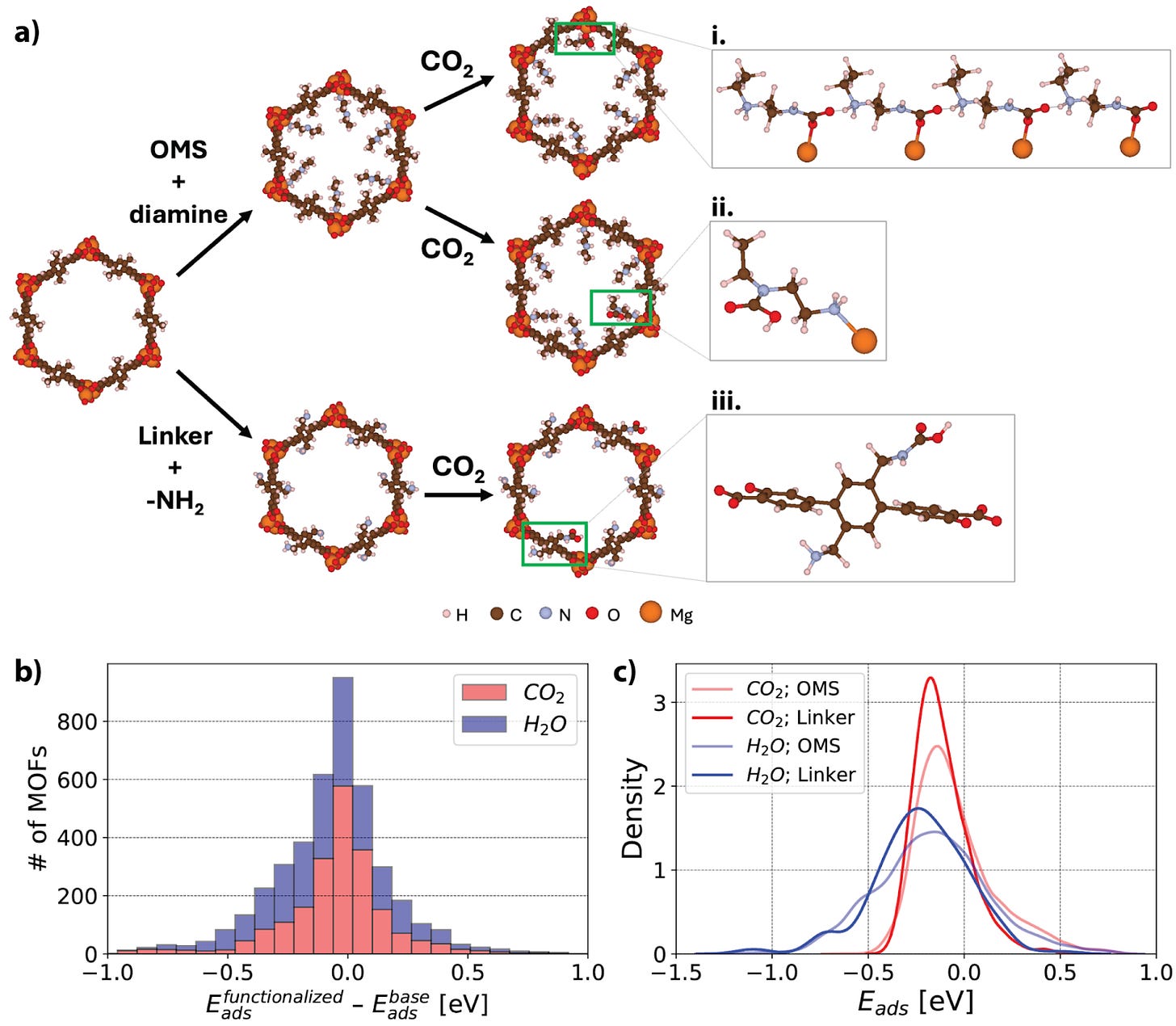

Figure 1: a) Representation of two different functionalizations of linker amination (bottom), and OMS diamine functionalization (top) introduced into the dataset of metal organic frameworks. IRMOF-74-III was used as a sample MOF. i. Demonstration of ion-paired cooperative formation for a carbamate chain provided CO2 is adsorbed onto metal amine lattices. ii. Carbamic acid, a sample variation of the reaction in ‘i.’ where instead of a 2:1 stoichiometry only a 1:1 stoichiometry exists. iii. Reacted product ‘ii’ for carbamic acid on MOF. b) Difference in most favourable adsorption energies between functionalized and non-functionalized MOFs for CO2 and H2O. c) Energy difference in amine-functionalized, and OMS functionalized, MOFs.

Finally, by introducing two different chemical functionalizations using i. amines and ii. OMS diamine a more diverse material space could be explored. Experimentally both linker- and OMS functionalization have been shown to enhance CO2 adsorption: the latter worked particularly well for environments with low CO2 partial pressures. As shown in figure b) and c) functionalization was found to increase adsorption probability for both CO2 and H2O.

So what are the next steps? Testing out the dataset in various environmental conditions. In the paper ODAC25 was compared against two other pretrained machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). However, it would be extremely interesting to see if predicted MOFs could be validated to indeed have higher absorption efficacy in real-world environments, installed above different industrial plant exhausts. A model could then be trained on the chemical ‘feasibility’ of synthesis, using this as a score to fine-tune and explore the space of MOFs generated in ODAC25 for specific applications. And, if proven correct, MOFs could be designed rationally for different exhaust combinations, providing optimal reaction surfaces that maximize CO2 capture for each plant. Linking MOFs and captured carbon varieties to downstream processes could even result in financial benefits from products that emerge. We stay on the lookout for individuals exploring the space.

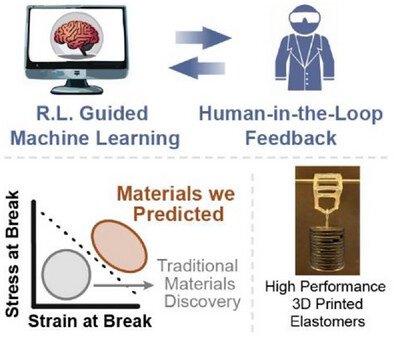

Chemists Can Discover New Materials More Quickly With AI [Kirsten Heuring, Carnegie Mellon University News, September 2025] & Design of Tough 3D Printable Elastomers with Human-in-the-Loop Reinforcement Learning [Rapp et al., Angewandte Chemie, July 2025]- HW

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and collaborators developed an AI system that accelerates the discovery of new polymers by helping chemists navigate the tradeoff between strength and flexibility—two properties that are traditionally difficult to optimize together. The machine learning model was trained on large datasets of known materials and can propose promising molecular structures that balance these competing attributes. This approach significantly reduces the trial-and-error cycle in the lab, enabling scientists to focus their experiments on the most likely candidates rather than testing thousands of possibilities.

Early applications have already identified a novel polymer with an unusually strong yet flexible profile, which could have an impact in areas like aerospace, biomedical devices, and sustainable packaging. Beyond this single discovery, the researchers highlight that the workflow is generalizable: AI can guide experimentalists toward efficient design strategies, making materials innovation more predictable and systematic. This integration of domain knowledge with data-driven models represents a shift toward collaborative “human-AI chemistry,” where computational tools complement scientific intuition to push the boundaries of material science.

Field Trip

Did we miss anything? Would you like to contribute to Decoding Science by writing a guest post? Drop us a note here or chat with us on Twitter: @pablolubroth @ameekapadia